Inappetence refers to a reduction in appetite and feed intake (synonymous with shy feeders).

For more information regarding inappetence in cattle see Shy Feeders.

Inanition is defined as the state of exhaustion resulting from lack of food and water. Inanition is used to describe deaths in the export industry due to prolonged refusal of food or inability to eat. Starvation refers similarly to the prolonged effects of deprivation of food or food refusal. Prolonged inappetence may progress to inanition and also results in increased risk of other conditions, such as salmonellosis causing severe and sometimes fatal infections in compromised animals.

Inanition and salmonellosis are the most common causes of death in exported sheep and goats and may occur separately (one disease resulting in death without evidence of the other) or together in the same animal. The first week of a sea voyage appears to present an elevated risk of salmonellosis, while inanition tends to occur more in later stages of a voyage.

Causal factors contributing to inappetence in sheep and goats are not well described. Adult sheep that are fat, exported during the second half of the year and coming from a high plane of nutrition are at a higher risk. In addition, feral goats appear to be at an elevated risk. Inappetence may appear in individual sheep or in lines of sheep. There also appear to be farm-level factors contributing to risk of inappetence such that some farms may be at higher risk than others.

It is presumed the stresses of transition from pasture to feedlot conditions may contribute to the risk of inappetence, including transport, curfew periods without feed or water, and transition to water troughs and pelleted feed. The greater appetite of younger, growing sheep, and sheep coming from a lower plane of nutrition is thought to protect animals from inappetence.

Most sheep that are inappetent in the assembly feedlot will start feeding during the early part of a voyage. However, inappetence in the feedlot is considered to indicate a higher risk of prolonged inappetence continuing during the voyage and an elevated likelihood of inanition and death.

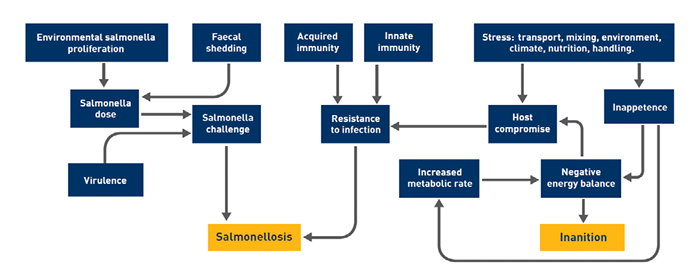

Figure 4.2: Unified causal web describing factors influencing risk of inappetence, salmonellosis and inanition in sheep (W.LIVE.0132)

Mortality studies in the late 1980s and early 1990s (LIVE.0112, 2002) suggested that persistent inappetence was the single major initiating condition that then led to elevated risk of subsequent occurrence of either inanition or salmonellosis (each associated with high mortality risk). Further studies (LIVE.0123, 2008; W.LIV.0132, 2009) have suggested that inappetence and salmonellosis may occur separately or together and the initial occurrence of either condition can then lead to increased risk of the other. The unified causal web presented in W.LIV.0132 (2009) and depicted in Figure 4.2, describes a complex pattern of causal factors that may lead to one or the other condition or both. The point of this is that control and prevention efforts need to be directed at both inappetence and salmonellosis and not just at inappetence.